KUHINA NUI, 1819-1864

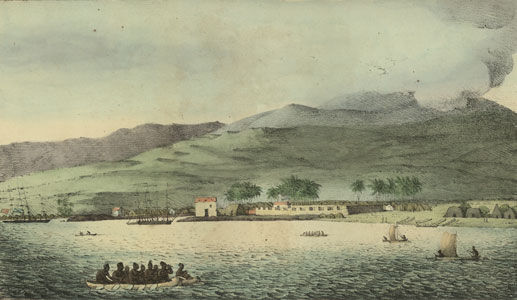

Vue de port hanarourou [View of the port of Honolulu], 1816-1817. Louis Choris, artist.

Published in Voyage Pittoresque du Autour du Monde, Paris, 1822.

From ancient times, Hawaiian kings ruled supreme, holding the power of life and death over their people. This tradition continued through the reign of Kamehameha I. When Kamehameha died in 1819, his realm had been exposed to outside influences for over forty years. Kamehameha’s heir, Liholiho, raised and trained in the traditional ways, was ill-equipped to cope with the rapid influx of foreign interests. Following his father’s death, Liholiho was proclaimed king. At his installation, Kamehameha I’s favorite wife, Ka‘ahumanu, expressed her intent to share the rule of the realm with Liholiho, and with her proclamation, the office of Kuhina Nui was created.

The Kuhina Nui was a unique position in the administration of Hawaiian government, and had no equivalent in western governments of the day. Erroneously translated as “premier” or “prime minister,” the office effectively, at least in its earlier years, was that of co-regent. The Kuhina Nui held equal authority to the king in all matters of government, including the distribution of land, negotiating treaties and other agreements, and dispensing justice.

The office of Kuhina Nui functioned from 1819 to 1864, through the reigns of Kamehameha II, III, IV, and V. Influenced by western-style government processes, Kamehameha III granted Hawai‘i’s first constitution in 1840 where the office of Kuhina Nui was first codified. The Constitution of 1852 further clarified some of the office’s responsibilities, including its authority in the event of the King’s death or minority of the heir to the throne.

As Hawai‘i became more integrated into the international community, governing required more expertise. In 1843, Kamehameha III began organizing a cabinet, by first appointing a minister of Foreign Affairs. Other ministries followed, including Interior and Finance, whose jurisdiction effectively replaced most of the Kuhina Nui’s responsibilities, making the position not only redundant, but an unnecessary oversight to the authority of the monarch. By the time Kamehameha V became king in 1863, almost all of the responsibilities of the Kuhina Nui had been assumed by the Kingdom’s ministers. Kamehameha V deliberately excluded the office in his constitution of 1864.

The Kuhina Nui was initially a position held by women of high chiefly rank. Six people would ultimately serve as Kuhina Nui: Ka‘ahumanu (1819-1832), Kīna‘u (1832-1839), Kekāuluohi (1839-1845), Keoni Ana (1845-1855), Victoria Kamāmalu (1855-1863), Mataio Kekūanāo‘a (1863-1864).